He writes:

One possible way of explaining these statistics, is that America experienced an explosion of racism over the past decade and white liberals are uniquely reflective of that change. But another possibility, perhaps more likely, is that ascendant progressive notions about race reflected in a steady drumbeat of reporting and editorializing on the subject from leading national media outlets, encouraged white liberals to label a larger number of behaviors and people as racist. In other words, while the world may have stayed more or less the same, elite liberal media and its readership—especially its white liberal readership—underwent a profound change.Let me offer a third possibility: That there is probably not that much more racism in America than there was 10 years ago, but that racists -- who empowered President Trump and were also empowered by him -- are more vocal and prominent in American life than they were a decade ago: The societal consensus that required racists to be careful and closeted has largely, but not entirely, disappeared. That has led to growing pressure from and within mainstream media outlets to call a thing a thing -- euphemisms like "racially charged" are now widely seen as weak tea, and there's a growing sense that the media doesn't have to be mindreaders to name a racist act a racist act.

Goldberg writes:

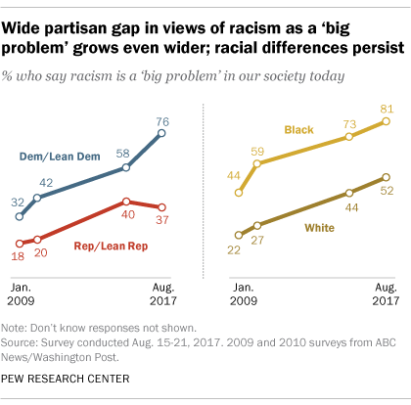

In 2011, just 35% of white liberals thought racism in the United States was “a big problem,” according to national polling. By 2015, this figure had ballooned to 61% and further still to 77% in 2017. ... Did white Democrats simply come to know more racists in these years? It’s possible, but if so that would indicate that the media’s increased reporting on racism actually correlated to a marked increase in racists being detected by white Democrats.

In other words, Goldberg's case is that the perception of racism in American life is pretty much a media-driven phenomenon -- manufactured by "woke" elites -- rather than events- or information-driven. But the rise in the use of the term racism, you'll see in the chart above, starts around 2011. That's when Donald Trump was going around TV promoting birtherism. In 2012, Trayvon Martin was killed. In 2014, the Black Lives Matter movement got started, with events in Ferguson helping spark a wave of protests -- and coverage. In 2015, Tanehisi Coates' "Between the World and Me" came out, giving many readers a sense of what America looks like through African-American eyes. And in 2016, Donald Trump was elected president of the United States. The period of increased "racism" coverage also coincides pretty much with the rise of viral videos depicting police brutality against black people. A lot of actual racism that was invsible to white liberals became more visible during this time. Alongside that, so did efforts to explain and understand the contours of that issue. "Did white Democrats simply come to know more racists in these years?" Goldberg asks. Unlikely, but it seems possible that white Democrats saw how other whites -- including folks they knew -- responded to events and concluded their circle of acquaintances probably contained more racism then they had previously realized.

It's also worth noting that Goldberg focuses his examination of the issue through the eyes of white liberals. In 2010, though, most Black Americans -- according to Pew Research -- already thought racism was a "big problem." The figure has only grown in recent years, but a lot of people for whom racism would actually be a big problem already thought it was a problem.

It's also worth noting that Goldberg focuses his examination of the issue through the eyes of white liberals. In 2010, though, most Black Americans -- according to Pew Research -- already thought racism was a "big problem." The figure has only grown in recent years, but a lot of people for whom racism would actually be a big problem already thought it was a problem.

No comments:

Post a Comment