I'm on record saying that the Arizona immigrant-profiling law is wrong, and I've used my forum with Scripps Howard to argue that

America would be better off with a sensible immigration policy that allows vastly more guest workers and other entrants into the United States legally. I think my lefty bona fides are established on the topic.

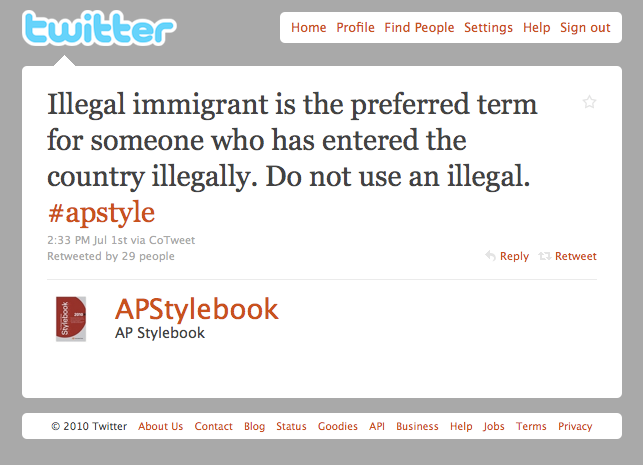

But this

Feministing blog post blasting AP Stylebook -- which guides the language standards in many, if not most, newsrooms through the country -- is just so much tedious sanctimony that I can barely stand it. Let's quote at length:

Screw you AP Style Book.

The AP Style Book is a resource for journalists on language, spelling, pronunciation and proper word usage. I'm not clear how the AP Style Book makes decisions, but it is widely regarded and highly used by journalists.

This explains why most of the mainstream media still uses the term "illegal immigrant." I find the term offensive and disrespectful, as do most immigration activists. People are not illegal, actions are. The advocate community uses the term "undocumented immigrant" which the Stylebook clearly disagrees with.

Thankfully, they don't advocate using the term "alien." But illegal needs to go.

But it's not the sensibilities of the "advocate community" that AP should worry about serving: It's the readers. And while Feministing makes the case that "undocumented immigrant" is somehow more accurate than "illegal immigrant," Feministing is ... wrong.

I get it: There's a desire to use language to create dignity for people by separating humanity's inherent characteristics from the conditions that afflict them and the actions they take. So there's no more "disabled person." It's now "person with disabilities."

The emphasis is on personhood. And that's nice. Laudable. But it does clutter the language: Two words become three. (Similarly, I know from painful experience that there's any number of neutered-but-nice terms for "homeless people.")

Pile up enough similar examples, and over time, the cluttering of language tends to obscure more than it reveals.

Which is the case with Feministing's snit: "Undocumented" reduces the issues at play to nothing more than a paperwork problem. (And it's not necessarily more accurate as shorthand; surely many if not most of these folks have, say, birth certificates or driver's licenses or whatnot in their home countries. What kind of documentation are we talking about?) "Illegal" more immediately conveys the sum and substance of the controversy -- and references to illegal immigration are almost always a reference to the controversy -- many people (and their American employers) have chosen to break the laws of this country by crossing the borders to work here.

I think those laws should change; I don't think playing games with the language is the way to do it.

As I suggested, any kind of shorthand -- whether it's "undocumented immigrant" or "illegal immigrant" -- is

always going to be overly reductive and, in the end, at least

somewhat imprecise. Some shorthand phrases, though, are more imprecise and convey less information than others. And those phrases should generally be avoided.