Showing posts with label occupy wall street. Show all posts

Showing posts with label occupy wall street. Show all posts

Saturday, December 31, 2011

I will defend to the death your right to burn the American flag

...but seriously, Occupy Charlotte people, you convince exactly nobody of the rightness of your cause when you do so. That's not effective dissent; it's masturbatory radicalism: It might make you feel good, but other people think it's icky and it's completely unproductive. Yeesh.

Sunday, December 4, 2011

Federalist 54, slavery, and 'The 1 Percent'

Like a lot of liberals, when I think about the Constitution's original provision that counted slaves as three-fifths of a person for the purpose of apportioning representation in Congress, I often think about it in racial terms: They were literally saying that black people were less than fully human! Sometimes I think about it in political terms: Southern politicians were accruing power—and thus preserving slavery—by giving slaves any human weight at all. But I don't often think about it in economic terms.

Federalist 54 changes that for me. This is the paper in which James Madison must justify the three-fifths apportionment to the people of New York. And his primary justification is this: Slaves are a form of wealth. And wealth deserves a little extra representation in the halls of government.

No really. This is what Madison writes:

The logic, as Madison admits, is "a little strained." If wealth determines representation, then why not make a tally of all the assets within a state and determine representation accordingly? The answer, it appears, is that slaves can be punished for committing crimes—that separates them from mere livestock, and, well, it all gets very depressing to read and think about.

But Federalist 54 is interesting in light of the recent "Occupy Wall Street" protests. At the heart of the demonstrations, I believe, is a belief that every citizen should have roughly equal representation in the federal government—the anger against "The 1 Percent" is anger not just that rich people are getting richer much faster than the rest of us, but that they have disproportionate influence with our government to bend policies to their will. To the protesters, that seems undemocratic—a betrayal of the American promise.

If we're to take Madison at his word, though, the problem is actually pretty foundational: The idea that wealth deserves more say in the halls of our democratic government seems at odds with the "one person, one vote" ideals we're usually taught, but it's baked into our government's DNA, part of the founding documents.

Federalist 54 changes that for me. This is the paper in which James Madison must justify the three-fifths apportionment to the people of New York. And his primary justification is this: Slaves are a form of wealth. And wealth deserves a little extra representation in the halls of government.

No really. This is what Madison writes:

"After all, may not another ground be taken on which this article of the Constitution will admit of a still more ready defense? We have hitherto proceeded on the idea that representation related to persons only, and not at all to property. But is it a just idea? Government is instituted no less for protection of the property, than of the persons, of individuals. The one as well as the other, therefore, may be considered as represented by those who are charged with the government. Upon this principle it is, that in several of the States, and particularly in the State of New York, one branch of the government is intended more especially to be the guardian of property, and is accordingly elected by that part of the society which is most interested in this object of government. In the federal Constitution, this policy does not prevail. The rights of property are committed into the same hands with the personal rights. Some attention ought, therefore, to be paid to property in the choice of those hands.Basically: Rich men have disproportionate influence on selecting representatives in government—more because of their awesomeness than because they purchase it seems—and so should rich states. That's why it's fair to (mostly) count slaves when determining a state's representation in the House of Representatives.

"For another reason, the votes allowed in the federal legislature to the people of each State, ought to bear some proportion to the comparative wealth of the States. States have not, like individuals, an influence over each other, arising from superior advantages of fortune. If the law allows an opulent citizen but a single vote in the choice of his representative, the respect and consequence which he derives from his fortunate situation very frequently guide the votes of others to the objects of his choice; and through this imperceptible channel the rights of property are conveyed into the public representation. A State possesses no such influence over other States. It is not probable that the richest State in the Confederacy will ever influence the choice of a single representative in any other State. Nor will the representatives of the larger and richer States possess any other advantage in the federal legislature, over the representatives of other States, than what may result from their superior number alone. As far, therefore, as their superior wealth and weight may justly entitle them to any advantage, it ought to be secured to them by a superior share of representation."

The logic, as Madison admits, is "a little strained." If wealth determines representation, then why not make a tally of all the assets within a state and determine representation accordingly? The answer, it appears, is that slaves can be punished for committing crimes—that separates them from mere livestock, and, well, it all gets very depressing to read and think about.

But Federalist 54 is interesting in light of the recent "Occupy Wall Street" protests. At the heart of the demonstrations, I believe, is a belief that every citizen should have roughly equal representation in the federal government—the anger against "The 1 Percent" is anger not just that rich people are getting richer much faster than the rest of us, but that they have disproportionate influence with our government to bend policies to their will. To the protesters, that seems undemocratic—a betrayal of the American promise.

If we're to take Madison at his word, though, the problem is actually pretty foundational: The idea that wealth deserves more say in the halls of our democratic government seems at odds with the "one person, one vote" ideals we're usually taught, but it's baked into our government's DNA, part of the founding documents.

Tuesday, November 29, 2011

Dirty hippies and the First Amendment

Regarding this: I’ve had to make this point a couple of times in the past few days, so I might as well make it here: You don’t have to *like* the Occupy folks to think that abusive policing is bad.

There’s an old saying that—in my view at least—once represented the American ideal: “I don’t like what you say, but I’ll defend to the death your right to say it.” That ideal has been replaced, it seems, with the idea that dirty hippies deserve whatever they get.

I like the old way better. It does require that I hold myself to the same ideal—that I allow room for people to be (say) bigoted or homophobic or, maybe, just a little too solicitous of the rich and powerful. I should defend their right to speak their minds, and get angry if a cop pepper sprays them for doing so. It’s easy to be gleeful when our opponents are silenced, but it isn't actually right.

There’s an old saying that—in my view at least—once represented the American ideal: “I don’t like what you say, but I’ll defend to the death your right to say it.” That ideal has been replaced, it seems, with the idea that dirty hippies deserve whatever they get.

I like the old way better. It does require that I hold myself to the same ideal—that I allow room for people to be (say) bigoted or homophobic or, maybe, just a little too solicitous of the rich and powerful. I should defend their right to speak their minds, and get angry if a cop pepper sprays them for doing so. It’s easy to be gleeful when our opponents are silenced, but it isn't actually right.

Monday, November 7, 2011

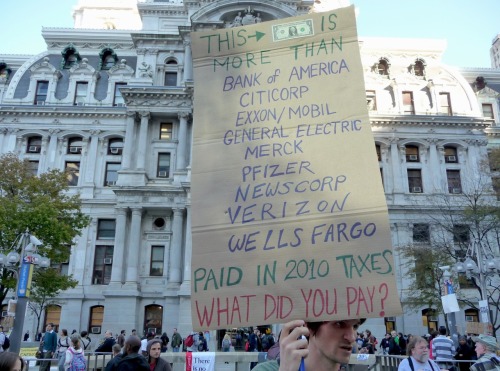

This is why there's an Occupy Wall Street movement

Because government helps banks, but it doesn't help you:

The largest banks are larger than they were when Obama took office and are nearing the level of profits they were making before the depths of the financial crisis in 2008, according to government data.

Stabilizing the financial system was considered necessary to prevent an even deeper economic recession. But some critics say the Bush administration, which first moved to bail out Wall Street, and the Obama administration, which ultimately stabilized it, took a far less aggressive approach to helping the American people.

“There’s a very popular conception out there that the bailout was done with a tremendous amount of firepower and focus on saving the largest Wall Street institutions but with very little regard for Main Street,” said Neil Barofsky, the former federal watchdog for the Troubled Assets Relief Program, or TARP, the $700 billion fund used to bail out banks. “That’s actually a very accurate description of what happened.”

A recent study by two professors at the University of Michigan found that banks did not significantly increase lending after being bailed out. Rather, they used taxpayer money, in part, to invest in risky securities that profited from short-term price movements. The study found that bailed-out banks increased their investment returns by nearly 10 percent as a result.

Sunday, October 30, 2011

Shut up and be happy, you ungrateful Occupy Wall Street protesters!

A conservative friend posted this to Facebook a couple of days ago, and it's been gnawing at me a bit:

The suggestion here being that the Occupy Wall Street crowd is selfish and ridiculous to be protesting.

This is both right and wrong. We should all be grateful in a cosmic sense for what we do have, of course. But "being a starving baby with ribs showing" shouldn't be the only grounds for complaint. (If it is, the Tea Party might want to pipe down as well.)

If you believe that your betters are tilting the playing field not through luck, not through accident, not merely through hard work, but through the greasing of palms and the escaping of the same rules that apply to you—then I think it's fine and appropriate to speak up.

This is a similar logic to those who suggest (say) American women shouldn't complain about disparities in the United States because, hey, Afghanistan! Burkhas! It's a logic that allows the people at the top to deflect the complaints (merited or not) of people in the middle and even people near the bottom—in in deflecting, serves those people at the top quite well.

It's also a logic at odds with the American Founding that conservatives like to claim as their unique heritage: The Founders might've been taxed without representation, but they were doing pretty well under the British, by and large. My conservative friend replies to this point that the Founders were concerned with "representation and consent of the governed. It wasn't simple materialism."

Well, exactly.

There are many Occupy Wall Street critics who have convinced themselves that the protests are, at foundation, envy by the poor of the rich. Perhaps there's some of that at work. But the most common complaint, as I understand it, is about governance. The fact that government is supposed to be accountable to people, but seems to be more responsive to moneyed interests—in ways that disadvantage many of us.

No: Things don't suck as much here as they might in other parts of the world. They might not suck as much as they did 100 or 200 years ago for many people. But it's not irrational to look at one's own time and place and ask if we could or should be doing better—and it's not selfish to push for that improvement if you can identify it.

The suggestion here being that the Occupy Wall Street crowd is selfish and ridiculous to be protesting.

This is both right and wrong. We should all be grateful in a cosmic sense for what we do have, of course. But "being a starving baby with ribs showing" shouldn't be the only grounds for complaint. (If it is, the Tea Party might want to pipe down as well.)

If you believe that your betters are tilting the playing field not through luck, not through accident, not merely through hard work, but through the greasing of palms and the escaping of the same rules that apply to you—then I think it's fine and appropriate to speak up.

This is a similar logic to those who suggest (say) American women shouldn't complain about disparities in the United States because, hey, Afghanistan! Burkhas! It's a logic that allows the people at the top to deflect the complaints (merited or not) of people in the middle and even people near the bottom—in in deflecting, serves those people at the top quite well.

It's also a logic at odds with the American Founding that conservatives like to claim as their unique heritage: The Founders might've been taxed without representation, but they were doing pretty well under the British, by and large. My conservative friend replies to this point that the Founders were concerned with "representation and consent of the governed. It wasn't simple materialism."

Well, exactly.

There are many Occupy Wall Street critics who have convinced themselves that the protests are, at foundation, envy by the poor of the rich. Perhaps there's some of that at work. But the most common complaint, as I understand it, is about governance. The fact that government is supposed to be accountable to people, but seems to be more responsive to moneyed interests—in ways that disadvantage many of us.

No: Things don't suck as much here as they might in other parts of the world. They might not suck as much as they did 100 or 200 years ago for many people. But it's not irrational to look at one's own time and place and ask if we could or should be doing better—and it's not selfish to push for that improvement if you can identify it.

Wednesday, October 26, 2011

Philadelphia: Does George Bochetto really pay more than half his income in taxes?

Stu Bykofsky, always the contrarian, uses his perch in the Philadelphia Daily News today to let the "Top 1 Percent" respond to the Occupy Wall Street protests. I found this excerpt to be particularly confounding:

Due respect to Bochetto and his rise to riches from the orphanage. Good for him! But does he really pay more than half his income to the government? If so, he needs to hire a new accountant—immediately.

Why do I say that? Because the effective tax rate for the top 1 percent of earners—and this combines and includes federal, state, and local taxes—was 30.9 percent in 2008. Here's a chart from Citizens for Tax Justice:

Granted, this is a national overview that's several years old. And granted, Philadelphia can be a little tougher on the pocketbook than a lot of places. But is it so much tougher that Bochetto loses and additional 20 percentage points off his income? Really, really doubtful—especially since the Social Security taxes actually take a bigger bite out of the incomes of low-wage earners than they do millionaires like Bochetto.

We can argue about appropriate tax rates and the responsibility of the rich to help provide services and opportunities for the rest of us. But that argument should be grounded in reality instead of unchallenged hyperbole. Bykofsky didn't help anybody by quoting Bochetto uncritically today.

How do the members of the "1 percent" feel? I asked three - Renee Amoore, Tom Knox and George Bochetto - each a local, unapologetic, self-made millionaire. They believe they already pay their "fair share" in federal taxes.

"I don't only pay the 35 percent," says Center City lawyer Bochetto, who was raised in an orphanage. "I also pay Social Security tax, state and city income tax, property tax. More than half of my income goes to the government. That's my fair share."

Due respect to Bochetto and his rise to riches from the orphanage. Good for him! But does he really pay more than half his income to the government? If so, he needs to hire a new accountant—immediately.

Why do I say that? Because the effective tax rate for the top 1 percent of earners—and this combines and includes federal, state, and local taxes—was 30.9 percent in 2008. Here's a chart from Citizens for Tax Justice:

Granted, this is a national overview that's several years old. And granted, Philadelphia can be a little tougher on the pocketbook than a lot of places. But is it so much tougher that Bochetto loses and additional 20 percentage points off his income? Really, really doubtful—especially since the Social Security taxes actually take a bigger bite out of the incomes of low-wage earners than they do millionaires like Bochetto.

We can argue about appropriate tax rates and the responsibility of the rich to help provide services and opportunities for the rest of us. But that argument should be grounded in reality instead of unchallenged hyperbole. Bykofsky didn't help anybody by quoting Bochetto uncritically today.

Wednesday, October 19, 2011

Why so many cops at Occupy Philly?

Juliana Reyes reports police lamentations that they're spending so much of their time and energy on the Occupy Philly protests:

The population at Occupy Philadelphia is ever in flux. But let's be generous and say there's as many as 500 people there during the day. (That may be an extremely high estimate: One Twitter observer counted 140 activists at Tuesday night's General Assembly.) That means there is one officer for every 17 protesters on the ground.

Now: Policing a protest is a little different at policing neighborhoods. And City Hall probably deserves a higher level of protection than many spaces. But there hasn't been much in the way of crime or violence at Occupy Philly—I'm certain it would be national news if it had happened—and there's no indication the campers are going to turn into an angry mob.

So why not put, say, half the Neighborhood Services Unit back on the streets doing their regular job? That way the unit can keep performing its duties—even at a reduced rate—and the protesters can enjoy a still-extraordinary level of police protection. As it stands, diverting the entire unit doesn't appear to be a smart use of the city's resources.

For the first week and a half that Occupy Philly held court in City Hall, the Police Department's entire Neighborhood Services Unit was detailed to the protest to watch over its participants. That means for that week and a half, the roughly 30-officer unit, whose responsibilities include responding to abandoned vehicle complaints, recovering stolen cars and investigating reports of short dumping and graffiti, didn't exist in the rest of the city.It's a shame that neighborhoods will go without the service—but is that necessary? Consider this: The entire Philadelphia Police Department has roughly 6,650 officers to police a city of 1.5 million people—roughly one officer per 225 residents.

NSU's Sgt. Frank Spires said that all 3-1-1 complaints, as well as direct calls to the unit, were shelved until the detail was over.

The population at Occupy Philadelphia is ever in flux. But let's be generous and say there's as many as 500 people there during the day. (That may be an extremely high estimate: One Twitter observer counted 140 activists at Tuesday night's General Assembly.) That means there is one officer for every 17 protesters on the ground.

Now: Policing a protest is a little different at policing neighborhoods. And City Hall probably deserves a higher level of protection than many spaces. But there hasn't been much in the way of crime or violence at Occupy Philly—I'm certain it would be national news if it had happened—and there's no indication the campers are going to turn into an angry mob.

So why not put, say, half the Neighborhood Services Unit back on the streets doing their regular job? That way the unit can keep performing its duties—even at a reduced rate—and the protesters can enjoy a still-extraordinary level of police protection. As it stands, diverting the entire unit doesn't appear to be a smart use of the city's resources.

Tuesday, October 18, 2011

Dennis Prager: Occupy Wall Street is like Hitler

Dennis Prager goes there in his column for NRO today:

Here's the problem: At least two of those three conditions aren't met in America today. First: Do the poor get to play under the same rules as the rich? We already know that if a poor man and a rich man step into court charged with the same crime, the rich man is much more likely to walk away free. Beyond the arena of criminal law, though, I outsource my commentary to one of Andrew Sullivan's readers:

How about the second leg? Can Americans live the Horatio Alger dream and transform themselves from nothing into something by dint of hard work? Maybe. But it doesn't seem to happen as often as it used to. The Brookings Institution (PDF) analyzed the situation in 2008:

Finally: Do the poor have their basic material needs met? Prager might have his strongest case here: America's poor are more likely to have cars, TVs, microwaves and other items that might be considered luxuries ... if one compares them to the very poorest people on earth. On the other hand, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (PDF) estimated in 2010 that 14.5 percent of all households were "food insecure" —meaning at some point in a year, there wasn't enough access to food "for an active,

healthy life for all household members." In 5.4 percent of households, some people had to do without meals because there wasn't enough money to buy food. But I acknowledge: Your mileage may vary whether you consider this an indictment of our entire society.

Still, it would seem by Prager's own estimation, we're facing a real problem of inequality in this country. The playing field isn't even and hard work (if you can find it) won't help you get ahead. Meanwhile, the rich can fail and still be fabulously successful—not because of nest eggs or smarts, but because the government had their backs.

I doubt that Prager would agree with this assessment. But in his leap to compare the OWS protesters to genocidal tyrants, he fails to consider that they might actually have something to protest against. He fails to contemplate that many of us who are sympathetic to the protesters don't hate the rich—we just don't want them consolidating their gains through government action unavailable to the rest of us. Some conservatives are sympathetic to that notion. Too bad Prager isn't.

The major difference between Hitler and the Communist genocidal murderers, Stalin, Mao, and Pol Pot, was what groups they chose for extermination.Yes, this is a column about the Occupy Wall Street movement. And it's clear that Prager would rather resort to tired old anti-Communist tropes rather than seriously examine the complaints of the protesters. Here's Prager, not getting it:

For Hitler, first Jews and ultimately Slavs and other “non-Aryans” were declared the enemy and unworthy of life.

For the Communists, the rich — the bourgeoisie, land owners, and capitalists — were labeled the enemy and regarded as unworthy of life.

Hitler mass-murdered on the basis of race. The Communists on the basis of class.

Being on the left means that you divide the world between rich and poor much more than you divide it between good and evil. For the leftist, the existence of rich and poor — inequality — is what constitutes evil. More than tyranny, inequality disturbs the Left, including the non-Communist Left. ... Non-leftists who cherish the American value of liberty over the left-wing value of socioeconomic equality, and those who adhere to Judeo-Christian values, do not regard the existence of economic classes as inherently morally problematic. If the poor are treated equally before the law, are given the chance and the liberty to raise their socioeconomic status, and have their basic material needs met, the gap between rich and poor is not a major moral problem.I'll distill that last sentence down to three rules: If the poor get to play by the same rules as the rich, have an opportunity for economic mobility, and can feed and house themselves, there's no problem.

Here's the problem: At least two of those three conditions aren't met in America today. First: Do the poor get to play under the same rules as the rich? We already know that if a poor man and a rich man step into court charged with the same crime, the rich man is much more likely to walk away free. Beyond the arena of criminal law, though, I outsource my commentary to one of Andrew Sullivan's readers:

When the financial industry came to the brink of collapse because of the reckless behavior of these "too big to fail" corporations, we saw an amazing ability for our government to come together to bail them out. In return, they've repaid the favor by working night and day to lift the already watered-down provisions of the Dodd-Frank reforms so they can continue with their same insanity, and to basically act like spoiled, entitled brats towards those of us who saved their butts in the first place.Rich financial institutions get bailed out; regular Americans are left to flounder. One of the three legs on Prager's stool is looking mighty shaky.

Contrast this with any legislation in Congress that might actually help out rank-and-file Americans, and suddenly everything becomes gridlocked and impossible to achieve. From out here, it appears that when you have a lobby on your side, government works, and if you don't, well tough luck.

How about the second leg? Can Americans live the Horatio Alger dream and transform themselves from nothing into something by dint of hard work? Maybe. But it doesn't seem to happen as often as it used to. The Brookings Institution (PDF) analyzed the situation in 2008:

The view that America is “the land of opportunity” doesn’t entirely square with the facts. Individual success is at least partly determined by the kind of familyIn short: If you're born rich or poor, you're likely to remain rich or poor. Those born middle class have more mobility up or down—but remember, this is before it became clear what devastation was being wrought by the Great Recession. In any case, you have a better chance of rising up if you're born in a socialist hellhole like Canada than you are in the United States. The opportunities just aren't there like they used to be. The second leg of Prager's three-legged stool is also increasingly shaky.

into which one is born. For example, 42 percent of children born to parents

in the bottom fifth of the income distribution remain in the bottom,

while 39 percent born to parents in the top fifth remain at the top. This is

twice as high as would be expected by chance. On the other hand, this

“stickiness” at the top and the bottom is not found for children born into

middle-income families. They have roughly an equal shot at moving

up or moving down and of ending up in a different income quintile than their parents.

There is less relative mobility in the United States than in many other

rich countries. One well-regarded study finds, for example, that the

United States along with the United Kingdom have a relatively low rate

of relative mobility while Canada, Norway, Finland, and Denmark

have high rates of intergenerational mobility. France, Germany, and

Sweden fall somewhere in the middle.

In sum: inequalities of income and wealth have clearly increased, but the

opportunity to win the larger prizes being generated by today’s economy

has not risen in tandem and has, if anything, declined.

Finally: Do the poor have their basic material needs met? Prager might have his strongest case here: America's poor are more likely to have cars, TVs, microwaves and other items that might be considered luxuries ... if one compares them to the very poorest people on earth. On the other hand, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (PDF) estimated in 2010 that 14.5 percent of all households were "food insecure" —meaning at some point in a year, there wasn't enough access to food "for an active,

healthy life for all household members." In 5.4 percent of households, some people had to do without meals because there wasn't enough money to buy food. But I acknowledge: Your mileage may vary whether you consider this an indictment of our entire society.

Still, it would seem by Prager's own estimation, we're facing a real problem of inequality in this country. The playing field isn't even and hard work (if you can find it) won't help you get ahead. Meanwhile, the rich can fail and still be fabulously successful—not because of nest eggs or smarts, but because the government had their backs.

I doubt that Prager would agree with this assessment. But in his leap to compare the OWS protesters to genocidal tyrants, he fails to consider that they might actually have something to protest against. He fails to contemplate that many of us who are sympathetic to the protesters don't hate the rich—we just don't want them consolidating their gains through government action unavailable to the rest of us. Some conservatives are sympathetic to that notion. Too bad Prager isn't.

Thursday, October 13, 2011

Walt Disney, Snow White, and Occupy Wall Street

At NRO, Charles C.W. Cooke finds an Occupy Wall Street protester to mock and educate. It needs to be quoted at length.

Until 1998, a movie like "Snow White"—that is, a work of "corporate authorship"—would've been under copyright for 75 years. Under that law, Disney's movie would've entered the public domain ... next year, making it possible for Cooke's protester to use the video in his mashup without fear. Something new and interesting might've been born of it.

But the Walt Disney corporation managed to use the power of its lobbying muscle to have the law revised with passage of the Copyright Term Extension Act. Now works of corporate authorship are protected for 120 years. "Snow White" won't be lawfully available for mashups until ... 2057. Assuming Disney hasn't had the law changed again by then.

There's a reason for copyrights—so that creators can reap the rewards of their work—but, once upon a time, there was a good reason for limited copyright terms: So other creators could take those ideas, build on them, create new innovations, and extend the vitality of capitalism.

And it's a good thing, too: "Snow White" was available for Walt Disney to use and fashion into something new, beautiful, and profitable because it was in the public domain. Walt Disney took risk, sure. His corporation is keeping others from acting similarly. That's not the "fair and square" victory Cooke claims.

He was a fairly well dressed and sometimes well spoken middle-aged man, and he wanted to talk to me about Walt Disney. This request alone was enough to pique my interest. But then, he surprised me. “Walt Disney,” he said, “was a whore…Look at how much money he made out of Snow White….Why can’t I use it in my mashups?”Actually, Walt Disney's corporation is a perfect example of how big corporations can bend the government to suit their purposes in ways that benefit them and crowd the public out of their own moneymaking and artistic endeavors.

Walt Disney made a lot of money from Snow White, something my friend considers unfair. But then Walt and his brother Roy also took a lot of risk. Originally estimating that the movie would cost $250,000 to make, the final bill ended up at around $1.5 million. During the three grueling years of production, Walt was almost universally laughed at for his ambition, including by his wife and brother. In the industry the project was known as “Disney’s Folly,” in part because the studio quite literally had to invent most of the processes necessary for the production of a full-length animated film. It had never been done before, and he was banking the studio’s future on it turning out alright. Through sheer will and charisma, and the hard if skeptical work of his brother Roy, Walt managed to borrow enough money to realize his vision. And here is the kicker — Walt remortgaged his house to help pay for it.

I told my friend this in response to his appraisal, albeit in less detail. His response: “So? I’ve lost my house twice.”

What we should have absolutely no sympathy for whatsoever, however, is the naked rejection of the American system, as espoused by my Disney-hating friend. Whatever one thinks of Wall Street, Walt Disney won fair and square and deserves our admiration not our oppobrium. It is this sort of attitude, encountered widely, that devastates the protester’s cause.

Until 1998, a movie like "Snow White"—that is, a work of "corporate authorship"—would've been under copyright for 75 years. Under that law, Disney's movie would've entered the public domain ... next year, making it possible for Cooke's protester to use the video in his mashup without fear. Something new and interesting might've been born of it.

But the Walt Disney corporation managed to use the power of its lobbying muscle to have the law revised with passage of the Copyright Term Extension Act. Now works of corporate authorship are protected for 120 years. "Snow White" won't be lawfully available for mashups until ... 2057. Assuming Disney hasn't had the law changed again by then.

There's a reason for copyrights—so that creators can reap the rewards of their work—but, once upon a time, there was a good reason for limited copyright terms: So other creators could take those ideas, build on them, create new innovations, and extend the vitality of capitalism.

And it's a good thing, too: "Snow White" was available for Walt Disney to use and fashion into something new, beautiful, and profitable because it was in the public domain. Walt Disney took risk, sure. His corporation is keeping others from acting similarly. That's not the "fair and square" victory Cooke claims.

Wednesday, October 12, 2011

About food stamps and millionaires

At National Review today, Robert Verbruggen urges the federal government to save (admittedly minimal) money by tightening standards for the food stamp program. Spending on the program, he says, has quadrupled during the last 10 years and standards are too loose:

This is in keeping with standard conservative rhetoric—going back to the time of Ronald Reagan's legendary "welfare queen"—that the people who receive safety benefits are somehow secretly well-off people who don't need the government largess. (It's only been a couple of months since National Review tried the same tack against a school-lunch program in Detroit.) That seems unlikely to be as effective an argument as it once was: Formerly middle-class suburbanites are a huge portion of the new food-stamp recipients. But the policies conservatives advocate aren't really designed to keep millionaires from getting food stamps—they're designed to keep poor people from getting food stamps.

Here's how you can tell: Verbruggen's example—a millionaire escapes his responsibilities because he receives his income not as "income" but as interest on investments—is also the fundamental scenario underlying President Obama's advocacy of the "Buffet rule." Some millionaires actually do pay lower tax rates, overall, than most middle-class folks because they receive most of their living money from capital gains, which are taxed at a much lower rate than ordinary income. Yet I doubt very much that Verbruggen would advocate increasing the tax rate on capital gains because of this situation.

Take a guess: Are millionaires more likely to avoid paying higher tax rates because of investment income, or more likely to use that income as a loophole to apply for food stamps? And which activity has a greater social impact?

This is one reason there is an Occupy Wall Street movement: Conservatives will defend millionaires from paying the same tax rates on investment income that you do on your work income—but they'll use that same investment income as a justification for undermining the safety net for the poor. It's almost as if Republicans were the party of the rich.

This has created some truly ridiculous situations — such as the case of a Michigan man who won $2 million in the lottery, tied it up in investments, and received so little income from them that he was still eligible for food stamps. Until a recent policy change, food-stamp eligibility in the state was based solely on income, with no consideration of savings accounts, investments, or other assets. Though the policy was set at the state level, federal taxpayers picked up the tab.But how many millionaires are gaming the system to get food stamps? I'm guessing maybe ... this guy. Maybe there are a few others out there. But I'll pull a number out of my posterior and guess that 99.99 percent of all food stamp recipients are not millionaires. And I defy anyone to prove otherwise.

This is in keeping with standard conservative rhetoric—going back to the time of Ronald Reagan's legendary "welfare queen"—that the people who receive safety benefits are somehow secretly well-off people who don't need the government largess. (It's only been a couple of months since National Review tried the same tack against a school-lunch program in Detroit.) That seems unlikely to be as effective an argument as it once was: Formerly middle-class suburbanites are a huge portion of the new food-stamp recipients. But the policies conservatives advocate aren't really designed to keep millionaires from getting food stamps—they're designed to keep poor people from getting food stamps.

Here's how you can tell: Verbruggen's example—a millionaire escapes his responsibilities because he receives his income not as "income" but as interest on investments—is also the fundamental scenario underlying President Obama's advocacy of the "Buffet rule." Some millionaires actually do pay lower tax rates, overall, than most middle-class folks because they receive most of their living money from capital gains, which are taxed at a much lower rate than ordinary income. Yet I doubt very much that Verbruggen would advocate increasing the tax rate on capital gains because of this situation.

Take a guess: Are millionaires more likely to avoid paying higher tax rates because of investment income, or more likely to use that income as a loophole to apply for food stamps? And which activity has a greater social impact?

This is one reason there is an Occupy Wall Street movement: Conservatives will defend millionaires from paying the same tax rates on investment income that you do on your work income—but they'll use that same investment income as a justification for undermining the safety net for the poor. It's almost as if Republicans were the party of the rich.

Monday, October 10, 2011

Sunday, October 9, 2011

What I saw at Occupy Philly

Occupy Philly: Oct 9, 2011 from Joel Mathis on Vimeo.

The Occupy Philly movement, as far as I can tell from my visit today, is dominated by neither fringe conspiracists nor the middle-class mainstream. Mostly, it seems to be made up of plucky twentysomethings who seem to have expected that the world they grew up in—the go-go 1990s and the "go shopping in the face of disaster" aughties—was the world they would inherit, and are cranky they didn't.

Yes, there were Marxists and Socialists and anarchists scattered among the crowd. But the tired "dirty, smelly hippie" stereotype doesn't fit what I found. Much of the crowd was, to all appearances, Standard Urban Hipster—not exactly suburbanites, exactly, but not nearly so outré as to alienate the masses either.

What it did seem to be, in fact, is a movement of privilege. The protesters were overwhelmingly white, overwhelmingly literate—and Philadelphia, for all its greatness, isn't really either. Most of the faces of color on Dilworth Plaza belonged, frankly, to homeless panhandlers who were sleeping there long before all the kids with liberal arts degrees showed up. Why not more minority participation? It could be that a big chunk of Philadelphia's population has gotten the short end of the stick for so long that the current crisis doesn't seem like that much of a crisis—only more of the same. The people who are protesting who the ones who had something to lose in the first place, and lost it.

For all that, there wasn't a lot of rage to be found at City Hall either. The spirit, in fact, seemed to be upbeat. Some protesters were helping gather and distribute food. There was a library set up, as well as an area for wi-fi use and tech support. One area was designated for a solar-powered battery to charge up; volunteers collected litter. There was even a stickball game on the north side. Speakers reminded the crowd that the plaza, for now, is their home—and to treat it as such. But far from the air of petulant, hypocritical entitlement that some media reports had led me to expect, what I found was a bunch of young people in the act of building—in miniature—the kind of society that they seek. That's nothing to scoff at.

Not that there weren't eye-rolling moments. One speaker exhorted protesters to use the readily available public toilets. "Please do not pee on your neighbors," he pleaded—apparently because that had already happened. A young woman took the mic and introduced her boyfriend, a young man who is on a hunger strike "until he gets some answers from Wall Street, or until medical professionals tell him to quit" the hunger strike.

Despite the crankiness at Wall Street—well-represented in the signs I photographed for the video above—I didn't see a ton of radicalism. Again, yes, the Marxists and the Socialists. But the angriest-sounding speaker inveighed heavily against corporate CEOs and their multimillion-dollar compensation packages—but added he didn't want to take those away: He just wants to ensure that everybody else can get by, too. Not exactly "when the revolution comes, you'll be first against the wall" stuff.

I do not know what Occupy Wall Street and all the related protests will become. Maybe they'll peter out. Maybe the fringe radicals will come to dominate. But that isn't what is happening right now. Right now, regular folks—young, smart, educated folks to be sure, but not weirdoes—are frustrated because they don't see a way to claim their piece of the American dream. And yeah: That should make the Top 1 percent very nervous.

Occupy Wall Street: No time for conspiracist nonsense

I'm headed down to City Hall in Philadelphia later today for a firsthand look at the Occupy Philadelphia movement. So I decided to check out the local website, and was greeted with this headline.

"Twelve families rule the world," eh? Google that phrase and you'll see that it's closely tied into conspiracy-minded nonsense that's a close cousin to anti-Semitic tropes that generally surface whenever protests against "bankers" get started. (Depending on how you search the phrase, the Wikipedia entry for the Rothschild family sometimes comes up fourth in the results. 'Nuff said.) And as much as I might be sympathetic to some of the movement's grievances, I'm not really interested in signing on for anti-Semitism or conspiracist nonsense. (To be fair, the Occupy Philly page also includes an essay from Chris Hedges, who warns against designating "Jews, Muslims" as enemies.)

Understand: Conspiracy theories—whether the "12 families" bit, or birtherism, or 9/11 trutherism—are almost always have no relation to the truth whatsoever. They're built on grievance and speculation, but not fact. Again: I'm not interested in signing onto a political movement with roots in angry fantasy.

Nor are most Americans, I suspect. Conspiracy-minded nonsense—in addition to being nonsense—is also a political loser. Birtherism doesn't help the Republican Party with independent voters, and crap about the Illuminati won't help the Occupy Wall Street movement build a critical mass of support either.

Conspiracism. Bad on the reality. Bad on the politics. I hope that when I go to City Hall today, I find something more grounded and less crazy than what the website offers. You can offer a critique of the status quo—and should, as far as I'm concerned—without resorting to fever dreams.

Update: The headline has been changed.

"Twelve families rule the world," eh? Google that phrase and you'll see that it's closely tied into conspiracy-minded nonsense that's a close cousin to anti-Semitic tropes that generally surface whenever protests against "bankers" get started. (Depending on how you search the phrase, the Wikipedia entry for the Rothschild family sometimes comes up fourth in the results. 'Nuff said.) And as much as I might be sympathetic to some of the movement's grievances, I'm not really interested in signing on for anti-Semitism or conspiracist nonsense. (To be fair, the Occupy Philly page also includes an essay from Chris Hedges, who warns against designating "Jews, Muslims" as enemies.)

Understand: Conspiracy theories—whether the "12 families" bit, or birtherism, or 9/11 trutherism—are almost always have no relation to the truth whatsoever. They're built on grievance and speculation, but not fact. Again: I'm not interested in signing onto a political movement with roots in angry fantasy.

Nor are most Americans, I suspect. Conspiracy-minded nonsense—in addition to being nonsense—is also a political loser. Birtherism doesn't help the Republican Party with independent voters, and crap about the Illuminati won't help the Occupy Wall Street movement build a critical mass of support either.

Conspiracism. Bad on the reality. Bad on the politics. I hope that when I go to City Hall today, I find something more grounded and less crazy than what the website offers. You can offer a critique of the status quo—and should, as far as I'm concerned—without resorting to fever dreams.

Update: The headline has been changed.

Saturday, October 8, 2011

Debt, and Occupy Wall Street

I've not yet been down to see the Occupy Philadelphia protest, though I hope to do so before the weekend is out. But reporter Kia Gregory has been down there this morning, Tweeting her observations. This one particularly struck me:

The Tea Party movement, you'll recall, began with Rick Santelli's famous rant against "losers" who'd fallen behind in their mortgage payments, defying the Obama-led government to do anything that might lessen the burden of those mortgages—because, after all, taxpayers shouldn't be on the hook for the unwise choices made by millions of individuals.

Admittedly, I think one of the wisest choices I made during the middle of the last decade was to not buy a house—despite a fair amount of peer pressure to do so. On the surface, there was plenty of reason to do so: I (at the time) had a solid career, loved the community was in, and expected to stay there a long time. Still: Buying a house looked likely to put me $150,000 or more in debt. An older colleague mocked me for my fear of such a substantial debt, suggesting I was avoiding the rites and even responsibilities of adulthood. But when circumstances changed—and then became more challenging—the lack of that $150,000 albatross around my neck gave me and my family a lot more freedom to make choices. The Philadelphia cardboard sign makes a really good point, it turns out.

But it's not been so long since we, as a society, had a very different attitude. Granted, it's an attitude my generation's grandparents—Depression-raised as they were—didn't seem to share. Debt wasn't a burden—it was "leverage," a way to get ahead, to "invest" in education or housing or (less crucially) a better SUV. If you could pay for those things with your own resources, super, but as my older colleague seemed to suggest, you were behaving counterproductively if you didn't take on the debt to get ahead.

Now, in a time of depressed housing prices and a high unemployment rate, that debt seems less like leverage and more like an anchor. I'm not sure what responsibility society—and taxpayers—have to the people who are now crushed by that burden. But society is not blameless in creating the problem in the first place. And I do suspect that the economy as a whole won't start to really move forward again until people feel like they can afford to buy stuff again (stimulating demand) instead of paying off their credit cards. There are probably two ways of doing that: Helping out the "losers" now, or settling in for a lost decade or more.

There is no freedom in debt. So what should we do about it?

The Tea Party movement, you'll recall, began with Rick Santelli's famous rant against "losers" who'd fallen behind in their mortgage payments, defying the Obama-led government to do anything that might lessen the burden of those mortgages—because, after all, taxpayers shouldn't be on the hook for the unwise choices made by millions of individuals.

Admittedly, I think one of the wisest choices I made during the middle of the last decade was to not buy a house—despite a fair amount of peer pressure to do so. On the surface, there was plenty of reason to do so: I (at the time) had a solid career, loved the community was in, and expected to stay there a long time. Still: Buying a house looked likely to put me $150,000 or more in debt. An older colleague mocked me for my fear of such a substantial debt, suggesting I was avoiding the rites and even responsibilities of adulthood. But when circumstances changed—and then became more challenging—the lack of that $150,000 albatross around my neck gave me and my family a lot more freedom to make choices. The Philadelphia cardboard sign makes a really good point, it turns out.

But it's not been so long since we, as a society, had a very different attitude. Granted, it's an attitude my generation's grandparents—Depression-raised as they were—didn't seem to share. Debt wasn't a burden—it was "leverage," a way to get ahead, to "invest" in education or housing or (less crucially) a better SUV. If you could pay for those things with your own resources, super, but as my older colleague seemed to suggest, you were behaving counterproductively if you didn't take on the debt to get ahead.

Now, in a time of depressed housing prices and a high unemployment rate, that debt seems less like leverage and more like an anchor. I'm not sure what responsibility society—and taxpayers—have to the people who are now crushed by that burden. But society is not blameless in creating the problem in the first place. And I do suspect that the economy as a whole won't start to really move forward again until people feel like they can afford to buy stuff again (stimulating demand) instead of paying off their credit cards. There are probably two ways of doing that: Helping out the "losers" now, or settling in for a lost decade or more.

There is no freedom in debt. So what should we do about it?

Thursday, October 6, 2011

Steve Jobs was capitalism at its best. Let's not make him the champion of capitalism at its worst.

Wednesday night, my Twitter feed—after the Phillies game ended—was primarily concerned with two things: Occupy Wall Street, and the death of Steve Jobs. It's terribly dangerous to mash up two wildly disparate news stories and find a Common Meaning in them, but I was struck nonetheless. And so I Tweeted my thoughts: That while capitalism has real, sometimes huge flaws, it is also capable—uniquely so, in my opinion—of offering us goods and services that help us survive, thrive, and extend our abilities. I think it's also largely true, as Rod Dreher said—and he, incidentally, is no fan of Big Corporatism—"socialism just doesn’t produce a Steve Jobs."

But I think National Review's Kevin D. Williamson takes the Jobs-as-awesome-capitalist meme too far:

Porn is hugely profitable. For that matter, so is selling meth. So is housing speculation—at least, until it isn't. And even Jobs' record on the front of "social value" isn't uncomplicated—witness the debate over working conditions at Apple's China factories.

The point here is not that Steve Jobs should be lumped in with flesh peddlers and junk dealers. He shouldn't. But Williamson writes that "economic answers can only satisfy economic questions"—and it's simply obvious that sometimes the answer is wrong. And sometimes, it can be very difficult to see that because of the profits involved. We are, in 2011—on the apparent cusp of a double-dip recession—living with proof of that.

Williamson concludes:

As my headline says: Steve Jobs is an example of capitalism at its finest. Conservatives like Williamson should take that example for what it's worth, instead of using it to argue for a fairy tale version of reality. There are flaws, and Jobs—for all his genius—wasn't completely exempt from them.

But I think National Review's Kevin D. Williamson takes the Jobs-as-awesome-capitalist meme too far:

Profits are not deductions from the sum of the public good, but the real measure of the social value a firm creates. Those who talk about the horror of putting profits over people make no sense at all. The phrase is without intellectual content. Perhaps you do not think that Apple, or Goldman Sachs, or a professional sports enterprise, or an internet pornographer actually creates much social value; but markets are very democratic — everybody gets to decide for himself what he values. That is not the final answer to every question, because economic answers can only satisfy economic questions. But the range of questions requiring economic answers is very broad.That phrase—that profits are "the real measure of the social value a firm creates"—strikes me as a bridge too far. Profits are one indicator, a significant one, but the real measure? There's no other good way to assess a firm's social value? No.

Porn is hugely profitable. For that matter, so is selling meth. So is housing speculation—at least, until it isn't. And even Jobs' record on the front of "social value" isn't uncomplicated—witness the debate over working conditions at Apple's China factories.

The point here is not that Steve Jobs should be lumped in with flesh peddlers and junk dealers. He shouldn't. But Williamson writes that "economic answers can only satisfy economic questions"—and it's simply obvious that sometimes the answer is wrong. And sometimes, it can be very difficult to see that because of the profits involved. We are, in 2011—on the apparent cusp of a double-dip recession—living with proof of that.

Williamson concludes:

And to the kids camped out down on Wall Street: Look at the phone in your hand. Look at the rat-infested subway. Visit the Apple Store on Fifth Avenue, then visit a housing project in the South Bronx. Which world do you want to live in?Well, no question: I'd rather live in the Apple Store. But I can't. The Apple Store is an advertisement, really, for Apple products specifically and the Apple ethos more generally. It's not a place I can live—advertising exists outside the realm of reality. Mistaking it for reality, as Williamson does here, doesn't do much to advance the cause of capitalism. Apple Stores are nice in part because poor people, generally, don't go in. That's not the case in the subway. But many of us need the subway to get to work—rat infestations and all—so that we can make the money we use to buy Steve Jobs' great products. That's a huge social good—it is an answer to an economic question, as Williamson says—and yet transit systems are pretty much never profitable.

As my headline says: Steve Jobs is an example of capitalism at its finest. Conservatives like Williamson should take that example for what it's worth, instead of using it to argue for a fairy tale version of reality. There are flaws, and Jobs—for all his genius—wasn't completely exempt from them.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Nothing good comes ever from this kind of talk. MAGA is going to end the American age, and it's possible that will turn out for the best...

-

Just finished the annual family viewing of "White Christmas." So good. And the movie's secret weapon? John Brascia. Who'...

-

Oh man, this describes my post-2008 journalism career: If I have stubbornly proceeded in the face of discouragement, that is not from confid...

-

John Yoo believes that during wartime there's virtually no limit -- legal, constitutional, treaty or otherwise -- on a president's p...