Let's forget political philosophy for a moment and focus only on math: At the moment, there is exactly one open job in America for every five people trying to find work. Even if every available spot were filled, 80 percent of the unemployed -- millions of Americans -- would still be unemployed. That's not because they're spoiled or lazy or intentionally unproductive. They're just unlucky.I wasn't thrilled to disclose my job status in the column -- the thing gets printed around the nation and even, on occasion, internationally -- but I felt duty-bound to share that I have a personal stake in this debate. I assure you, though, that my opinions would've been the same either way.

Today's critics of unemployment insurance suggest the system takes money from productive citizens and gives it to the unproductive.

Perhaps. But those "productive" citizens should understand that they're not just throwing money down a rat hole -- they're buying civilization.

Look back at the origins of unemployment insurance. The Great Depression hit America in 1929, and unemployment rates soared far beyond the current crisis. In 1932, a "Bonus Army" of 17,000 unemployed World War I veterans marched on Washington D.C. -- and were dispersed with deadly force. Capitalism and the American system stood at the brink.

The Social Security Act of 1935 -- which created our modern unemployment insurance system -- helped change that. Workers and their families suddenly had breathing room when work disappeared. They were able to pay their mortgages, buy food and keep participating in the economy. That made them less inclined to act desperately -- and the "trickle up" effect helped keep other merchants in business.

Capitalism survived and thrived.

Our 21st-century economy isn't quite as dire, but the lessons from that era are still true. And it's reprehensible that Republicans like Sharron Angle treat hard-luck Americans like they're parasites.

Full disclosure: I've been collecting unemployment benefits while seeking a full-time job. I've also found part-time work and freelance writing gigs to supplement that income. So I certainly don't feel spoiled or lazy. I have, however, learned the value of a strong safety net.

Thursday, July 8, 2010

Do unemployment benefits "spoil" Americans for real work?

That's the topic of this week's column with Ben Boychuk for Scripps Howard News Service -- inspired by Sharron Angle's comments in Nevada. My take:

Victor Davis Hanson: Higher taxes are part of restoring American greatness

At National Review, Victor Davis Hanson warns against those who see America in decline. Things could easily get better, quickly, he says, and offers up a list of reasons why. And one of those reasons is rather extraordinary:

Realistically, though, getting deficits and debts under control will take some combination of higher taxes and reined-in spending. Republicans generally offer only the second of that equation -- and then usually (but not only) rhetorically. (It can be argued Democrats have precisely the opposite problem.) Victor Hanson Davis -- in a rare non-Dowdian moment -- actually seems somewhat realistic today. Does he know what he just did? Do National Review's editors?

We are soon to revert to the Clinton income-tax rates last used in 2000, when we ran budget surpluses. If likewise we were to cut the budget, or just hold federal spending to the rate of inflation, America would soon run surpluses as it did a decade ago. For all our problems, the United States is still the largest economy in the world, its 300 million residents producing more goods and services than the more than 1 billion in either China or India.But... but... conservatives at National Review and elsewhere have been stomping their feet for the last 18 months about the restoration of Clinton-era marginal tax rates! Along with spending on TARP, the stimulus bill and health care bill, letting Bush-era tax cuts expire has been a central tenet of the Tea Party/conservative case that President Obama is spreading creeping socialism across this once-great land! The tax increases, in other words, are supposedly one reason for the sense of American decline.

Realistically, though, getting deficits and debts under control will take some combination of higher taxes and reined-in spending. Republicans generally offer only the second of that equation -- and then usually (but not only) rhetorically. (It can be argued Democrats have precisely the opposite problem.) Victor Hanson Davis -- in a rare non-Dowdian moment -- actually seems somewhat realistic today. Does he know what he just did? Do National Review's editors?

Wednesday, July 7, 2010

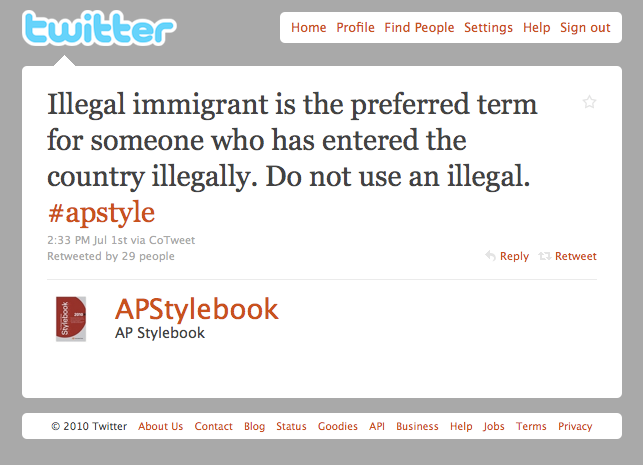

AP Stylebook, Feministing and the language of illegal immigration

I'm on record saying that the Arizona immigrant-profiling law is wrong, and I've used my forum with Scripps Howard to argue that America would be better off with a sensible immigration policy that allows vastly more guest workers and other entrants into the United States legally. I think my lefty bona fides are established on the topic.

But this Feministing blog post blasting AP Stylebook -- which guides the language standards in many, if not most, newsrooms through the country -- is just so much tedious sanctimony that I can barely stand it. Let's quote at length:

I get it: There's a desire to use language to create dignity for people by separating humanity's inherent characteristics from the conditions that afflict them and the actions they take. So there's no more "disabled person." It's now "person with disabilities." The emphasis is on personhood. And that's nice. Laudable. But it does clutter the language: Two words become three. (Similarly, I know from painful experience that there's any number of neutered-but-nice terms for "homeless people.") Pile up enough similar examples, and over time, the cluttering of language tends to obscure more than it reveals.

Which is the case with Feministing's snit: "Undocumented" reduces the issues at play to nothing more than a paperwork problem. (And it's not necessarily more accurate as shorthand; surely many if not most of these folks have, say, birth certificates or driver's licenses or whatnot in their home countries. What kind of documentation are we talking about?) "Illegal" more immediately conveys the sum and substance of the controversy -- and references to illegal immigration are almost always a reference to the controversy -- many people (and their American employers) have chosen to break the laws of this country by crossing the borders to work here. I think those laws should change; I don't think playing games with the language is the way to do it.

As I suggested, any kind of shorthand -- whether it's "undocumented immigrant" or "illegal immigrant" -- is always going to be overly reductive and, in the end, at least somewhat imprecise. Some shorthand phrases, though, are more imprecise and convey less information than others. And those phrases should generally be avoided.

But this Feministing blog post blasting AP Stylebook -- which guides the language standards in many, if not most, newsrooms through the country -- is just so much tedious sanctimony that I can barely stand it. Let's quote at length:

Screw you AP Style Book.

The AP Style Book is a resource for journalists on language, spelling, pronunciation and proper word usage. I'm not clear how the AP Style Book makes decisions, but it is widely regarded and highly used by journalists.

This explains why most of the mainstream media still uses the term "illegal immigrant." I find the term offensive and disrespectful, as do most immigration activists. People are not illegal, actions are. The advocate community uses the term "undocumented immigrant" which the Stylebook clearly disagrees with.

Thankfully, they don't advocate using the term "alien." But illegal needs to go.But it's not the sensibilities of the "advocate community" that AP should worry about serving: It's the readers. And while Feministing makes the case that "undocumented immigrant" is somehow more accurate than "illegal immigrant," Feministing is ... wrong.

I get it: There's a desire to use language to create dignity for people by separating humanity's inherent characteristics from the conditions that afflict them and the actions they take. So there's no more "disabled person." It's now "person with disabilities." The emphasis is on personhood. And that's nice. Laudable. But it does clutter the language: Two words become three. (Similarly, I know from painful experience that there's any number of neutered-but-nice terms for "homeless people.") Pile up enough similar examples, and over time, the cluttering of language tends to obscure more than it reveals.

Which is the case with Feministing's snit: "Undocumented" reduces the issues at play to nothing more than a paperwork problem. (And it's not necessarily more accurate as shorthand; surely many if not most of these folks have, say, birth certificates or driver's licenses or whatnot in their home countries. What kind of documentation are we talking about?) "Illegal" more immediately conveys the sum and substance of the controversy -- and references to illegal immigration are almost always a reference to the controversy -- many people (and their American employers) have chosen to break the laws of this country by crossing the borders to work here. I think those laws should change; I don't think playing games with the language is the way to do it.

As I suggested, any kind of shorthand -- whether it's "undocumented immigrant" or "illegal immigrant" -- is always going to be overly reductive and, in the end, at least somewhat imprecise. Some shorthand phrases, though, are more imprecise and convey less information than others. And those phrases should generally be avoided.

Innocence, justice, and Antonin Scalia: Why I'm rooting for Elena Kagan

Radley Balko notes that the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals is refusing to hear the habeas corpus petition of a man who has established his innocence in the sex crimes for which he was convicted. Why the rejection? Because the dude filed his petition after the deadline.

Balko:

Balko:

By the panel’s reckoning, adherence to an arbitrary deadline created by legislators is a higher value than not continuing to imprison people we know to be innocent.The circuit court's decision is horrifying -- but its logic isn't that surprising. Why? Because that's the exact same logic that Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia has used. Remember this?

This Court has never held that the Constitution forbids the execution of a convicted defendant who has had a full and fair trial but is later able to convince a habeas court that he is "actually" innocent. Quite to the contrary, we have repeatedly left that question unresolved, while expressing considerable doubt that any claim based on alleged "actual innocence" is constitutionally cognizable.And this is why I'd rather see Elena Kagan, Sonia Sotomayor or any other "empathetic" judge on the court than some Scalia wannabes who are faithful to a very narrow interpretation of the Constitution. Fidelity to the law is important; fidelity to justice, while perhaps more abstract, is also important. Antonin Scalia's jurisprudence is one that easily lets people be executed or rot in jail for crimes they didn't commit. And Republicans regularly name him the justice they love most. Horrifying.

Tuesday, July 6, 2010

Republicans would rather be Cobra Kai than turn up the thermostat

In perhaps the clearest-ever expression of the Republican id, Victorino Matus responds with disgust to a scene in the new "Karate Kid" movie that features Jackie Chan urging apartment tenants to only heat water for a shower when they're about to take a shower -- instead of having hot water constantly on demand. Chan's line: "Put in a (hot water) switch and save the planet.)

Matus' response:

It's enough to make you want to join the Cobra Kai, show no mercy, and put 'em in a body bag.I've said before that one reason I knew that torture is bad is because during the 1980s, "Rambo" showed it being done by Communist Russians and Vietnamese. I know Matus is joking here -- kind of -- but it does seem as though Republicans are journeying to the dark side by embracing every villain and villainous deed from the most popular movies of the Reagan Decade. At this rate, the GOP will soon be defending its foreign policy ideas by invoking "diplomatic immunity."

Dear Citizens United: What does "Stop Iran Now" mean?

I bet you can't guess which 20th century historical analogy is used in this Citizens United ad urging President Obama to "Stop Iran Now."

Oh wait. I bet you can.

Put aside the self-parodying hilarity of the right's ability to see every single foreign policy challenge as 1938 revisited. Here's a question for Citizens United:

What the heck does "Stop Iran Now" mean?

I've got a guess. It probably doesn't -- judging from the D-Day footage used in the ad above -- involve sanctions and diplomacy. It probably involves bombs and destruction and, well, war.

But try as I might, I can't find any statement on the Citizens United site -- or on any of the StopIranNow.com feeds -- thatsuggests explicitly calls for a precise course of action. There's nothing at the StopIranNow.com site, as of this writing, except this video.

Why so coy?

Such vague apparent but plausibly denied warmongering leaves me believe one of two possibilities: The "Stop Iran Now" folks don't have the courage of their convictions, which is why they remain somewhat murky. Or the ad isn't really about Iran at all -- it's purely about trying to make the president look weak and, well, Neville Chamberlainish. It's aggressive passive aggression, but despite being promoted by outlets like The Weekly Standard -- or maybe because of that -- it shouldn't be taken seriously as anything ther than politics.

Oh wait. I bet you can.

Put aside the self-parodying hilarity of the right's ability to see every single foreign policy challenge as 1938 revisited. Here's a question for Citizens United:

What the heck does "Stop Iran Now" mean?

I've got a guess. It probably doesn't -- judging from the D-Day footage used in the ad above -- involve sanctions and diplomacy. It probably involves bombs and destruction and, well, war.

But try as I might, I can't find any statement on the Citizens United site -- or on any of the StopIranNow.com feeds -- that

Why so coy?

Such vague apparent but plausibly denied warmongering leaves me believe one of two possibilities: The "Stop Iran Now" folks don't have the courage of their convictions, which is why they remain somewhat murky. Or the ad isn't really about Iran at all -- it's purely about trying to make the president look weak and, well, Neville Chamberlainish. It's aggressive passive aggression, but despite being promoted by outlets like The Weekly Standard -- or maybe because of that -- it shouldn't be taken seriously as anything ther than politics.

Monday, July 5, 2010

Hello, Paro: I for one, welcome our new robot caregiver overlords

The New York Times has a fascinating story today about how robots are increasingly being used for caregiver functions -- "Paro," a robot critter that looks like a baby seal, is used to provide comfort and friendship to the elderly in nursing homes -- and raises an interesting ethical dilemma:

Turkle's question -- who will deserve people? -- raises another. Why not people? Why not pets? Why spend $1,000 on a fake baby seal when there's somebody's grandson who could come in for free?

Some social critics see the use of robots with such patients as a sign of the low status of the elderly, especially those with dementia. As the technology improves, argues Sherry Turkle, a psychologist and professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, it will only grow more tempting to substitute Paro and its ilk for a family member, friend — or actual pet — in an ever-widening number of situations.What's fascinating about Paro, to me, is that the rise of technology has increasingly made our world less organic -- most of us are, of course, sealed up in air-conditioned bubbles for the vast majority of our lives, cut off from the realm of, well, experience. But as Paro demonstrates, the aim of much technological research is to duplicate (using circuitry) that which already exists in the realm of flesh, blood and bone.

“Paro is the beginning,” she said. “It’s allowing us to say, ‘A robot makes sense in this situation.’ But does it really? And then what? What about a robot that reads to your kid? A robot you tell your troubles to? Who among us will eventually be deserving enough to deserve people?”

Turkle's question -- who will deserve people? -- raises another. Why not people? Why not pets? Why spend $1,000 on a fake baby seal when there's somebody's grandson who could come in for free?

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

-

Just finished the annual family viewing of "White Christmas." So good. And the movie's secret weapon? John Brascia. Who'...

-

When rumors surfaced Monday that Philly schools Superintendent Arlene Ackerman might be leaving town, I was hopeful. Not just because her ad...

-

Warning: This is really gross. When the doctors came to me that Saturday afternoon and told me I was probably going to need surgery, I got...