Saturday, June 18, 2011

Netflix Queue: "A World Without Thieves"

Truth is, I'll watch anything with Andy Lau in it—the stuff that makes it to America (like, most notably, "Infernal Affairs") is generally entertaining—and so is this. Here, Lau plays one half of a grifting couple that decides to protect an innocent young man traveling on a train with his life savings. The moments where Lau tangles with another gang of grifters are quietly thrilling; the movie takes me back 30 years, when big movie studios made quiet, entertaining dramas instead of farming them out to the indies and boutique divisions for Oscar bait. A pleasant Saturday night diversion.

Friday, June 17, 2011

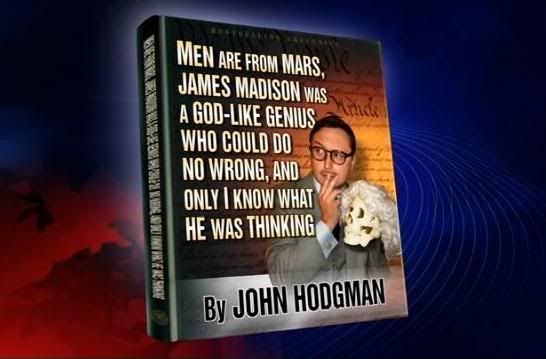

The sheer tediousness of Ben Shapiro's anti-Hollywood crusade

|

| Ben Shapiro |

Ross Gellar (Friends, 1994-2004) What is Ross doing on this list? He’s here because he represents the left’s next step: the absentee father who simply doesn’t matter to his son’s life. Ross impregnates his lesbian wife, has a kid, and then takes care of the kid once every blue moon between his affairs and antics. His son, Ben, never feels any ill effects. Welcome to the liberal paradise, where dads are completely superfluous.This is just ... so ... tedious. And it also reflects why Shapiro and his ilk don't do very well in advancing a conservative agenda through popular entertainment: He's concerned exclusively about the agenda, and almost not at all about the entertainment.

The Friends example is probably the most revealing of this mindset. Was Friends a show about family or parenthood? Nope. It was about a group of ... Friends. Young, attractive people who had the freedom to do wacky things and live in New York apartments far beyond their likely incomes. Was Ross a father in the show? Sure. But the reason we didn't see Ross parenting much is because the show wasn't about that. The relationship with his son served as fodder for an episode or two, and that's all it was designed to do: be an excuse for an occasional story. In Shaprio's hands, Friends would've either become a family sitcom like Leave It To Beaver—and not been the show it was, but some other show entirely—or else Ross's son Ben would've descended into a life of drugs, crime, and despair. That would've been a great sitcom!

If you look at Shapiro's list of dads, only three—Archie Bunker, Cliff Huxtable, and Cameron/Mitchell from Modern Family—can plausibly be claimed to be serving somebody's political agenda. But Shapiro sees all of them, in every show, through the lens of ideology, can only conceive of entertainment as agitprop, and does not conceive of a world where the main agenda is getting a good laugh or telling a rollicking yarn.

And it's really, really, excruciatingly tedious.

If you want a contrast, check out Alyssa Rosenberg's culture blog at Think Progress. Rosenberg frequently views popular culture through liberal, feminist lenses. But sometimes she just enjoys a good book, or a good movie, or a good show, all without getting hung up on whether it's liberal enough. It makes one wish that Shapiro could stock up on junk food, head to the basement, and spend a weekend in his underwear watching so-bad-they're-good movies from the 1980s.

Do liberals run Hollyood? Maybe. But on the evidence of Shapiro's perpetual whining, that's the way I prefer it. Ideology or no, liberals—in the storytelling realm, at least—are way, way more fun.

Ed Rendell and why we can't afford the death penalty in Pennsylvania

I'm pretty stoutly against the death penalty, but I'm often unsure that I should write about it—because, as a practical matter, Pennsylvania doesn't ever really put anybody to death. Still, the legal and theoretical existence of the death penalty skews the justice system here in undesirable ways—and Ed Rendell, to his credit, is trying to do something about it:

Now, I'm not in a position to turn down a $2,000 paycheck. But when you think about the time it must take to prepare a proper defense in capital murder trial, that preparation fee is incredibly low. Google doesn't offer me a ready-made estimate of defense billable hours in death penalty cases around the nation, but it's not uncommon to see figures like 463 hours—or many, many more—thrown around.

One wonders if a capital defense lawyer in Pennsylvania ends up making even minimum wage on a case. But this is troubling—and unjust—because prosecutors surely aren't limited to $2,000 of pay in preparing for a capital case. While government prosecutors don't have an unlimited budget, their resources simply overwhelm those of an indigent murder defendant. When the trial starts, the playing field is already weighted heavily toward the prosecution.

It's not supposed to work that way.

Rendell is trying to do something about it by getting a raise for defense attorneys because of that imbalance. "It results in a tremendous waste of money, but, far more importantly, it increases the very real possibility that someone who is not guilty or not deserving of the death penalty could be convicted and sentenced to death." He's right. But he's wrong about the solution.

Pennsylvania's budget--like government budgets everywhere--is coming down. There is no more money for defense attorneys, and it's never politically popular to increase spending on defendants anyway. The best way to ensure that capital murder defendants have something approaching a fair chance in Pennsylvania courts is to end the death penalty, once and for all.

This isn't about whether guilty defendants deserve to die. It's about whether the state can fairly administer justice, whether it can ensure that a condemned man legitimately deserves that condemnation. Right now, that doesn't appear to be the case. And since death row appears to mostly be a life sentence, anyway, the added costs of a capital murder trial seem wasted—if the intended result is an execution.

Death penalty jurisprudence in Pennsylvania is unbalanced, unfair, and ultimately ineffective. Why are we holding onto this system?

Rendell, a former Pennsylvania governor and the city's district attorney from 1978 to 1986, has written to Common Pleas Court President Judge Pamela Pryor Dembe urging her to administratively increase the flat-fee system now being challenged before the state Supreme Court.Emphasis added. Now, that $2,000 just covers "trial preparation" time—defense lawyers get paid $200-$400 a day during the actual trial.

The petition on behalf of three Philadelphians facing death if convicted of murder contends that the $2,000 flat rate paid court-appointed capital lawyers is so low that it violates the clients' constitutional right to "effectiveness of counsel."

Now, I'm not in a position to turn down a $2,000 paycheck. But when you think about the time it must take to prepare a proper defense in capital murder trial, that preparation fee is incredibly low. Google doesn't offer me a ready-made estimate of defense billable hours in death penalty cases around the nation, but it's not uncommon to see figures like 463 hours—or many, many more—thrown around.

One wonders if a capital defense lawyer in Pennsylvania ends up making even minimum wage on a case. But this is troubling—and unjust—because prosecutors surely aren't limited to $2,000 of pay in preparing for a capital case. While government prosecutors don't have an unlimited budget, their resources simply overwhelm those of an indigent murder defendant. When the trial starts, the playing field is already weighted heavily toward the prosecution.

It's not supposed to work that way.

Rendell is trying to do something about it by getting a raise for defense attorneys because of that imbalance. "It results in a tremendous waste of money, but, far more importantly, it increases the very real possibility that someone who is not guilty or not deserving of the death penalty could be convicted and sentenced to death." He's right. But he's wrong about the solution.

Pennsylvania's budget--like government budgets everywhere--is coming down. There is no more money for defense attorneys, and it's never politically popular to increase spending on defendants anyway. The best way to ensure that capital murder defendants have something approaching a fair chance in Pennsylvania courts is to end the death penalty, once and for all.

This isn't about whether guilty defendants deserve to die. It's about whether the state can fairly administer justice, whether it can ensure that a condemned man legitimately deserves that condemnation. Right now, that doesn't appear to be the case. And since death row appears to mostly be a life sentence, anyway, the added costs of a capital murder trial seem wasted—if the intended result is an execution.

Death penalty jurisprudence in Pennsylvania is unbalanced, unfair, and ultimately ineffective. Why are we holding onto this system?

Mandatory sick leave: It's not just Philadelphia

City Council approved a mandatory sick leave bill yesterday—Mayor Nutter has promised a veto. But Philadelphia isn't the only place this debate is playing out: Connecticut just passed a law, and several other states and cities are considering it. That's why Ben and I tackle the issue in our Scripps Howard column this week. My take:

Here is what opponents of paid sick leave apparently desire: that you enter a local restaurant for a delicious meal prepared by a flu-ridden cook who can't afford to take the day off -- or else her own kids might have to do without a meal of their own. Enjoy your Virus Burger, folks!Ben: "Don't be surprised if unemployment remains high if these bills pass."

Hyperbolic? A little. But the reason the sick-leave moment exists is that many low-paid workers often have to choose between working sick -- or leaving sick children at home -- or losing desperately needed income.

Business owners are understandably concerned that such a requirement would cut into their revenues, and possibly make it impossible to do business. Their concerns are fueled by studies that exaggerate the potential costs by assuming -- implausibly -- that workers would take every possible day of sick leave. An additional underlying belief is that businesses see little or no benefit from offering such benefits to their employees.

Neither belief is warranted. In Connecticut, for example, the Economic Policy Institute discovered that employees who already had access to five paid sick days took off just 2.41 of those days.

And while advocates for paid sick leave say that a national law would cost businesses $20.2 billion, those same businesses would reap $28.4 billion by reducing job turnover and lost productivity from workers who show up ill and can't properly perform their duties.

In these dark economic times, policymakers understandably hesitate to add to the burdens of small businesses. It would be nice if government could provide incentives to business to provide sick leave, instead of merely piling on new regulations.

The underlying principle of such proposals is sound, however: Jobs should offer more than a labor opportunity-- they should offer a living.

If that means you eat a hamburger with fewer germs, so much the better.

Thursday, June 16, 2011

A theory about Anthony Weiner, Democrats and strong women

I expect this is the last time I write about Anthony Weiner, but I do wonder if his resignation today doesn't have something to do with the fact that there are actual women in the Democratic leadership, both in the House and in the broader party.

Remember, it was after Weiner confessed to his lewd online communications and vowed not to resign that House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi said he should resign: He'd lied to her, after all, claiming he wasn't responsible for the first incriminating photo. Pelosi was followed by DNC Chairwoman Debbie Wasserman Schultz. And there were lots of behind-the-scenes reports that Secretary of State Hillary Clinton—the friend and boss of Weiner's wife—was exceedingly furious with him. When Pelosi started the effort to take a powerful committee assignment from Weiner, the game was up: He quit. But the pattern is clear—the post-confession drive to get Weiner from office didn't seem to come from his constituents or even from Republicans, who seemed happy to let him twist in the wind. It came from powerful Democratic women.

Contrast this with some of the higher-profile Republican scandals of recent vintage. Sure, Christopher Lee resigned, but David Vitter went to see a hooker—and got re-elected! John Ensign's Christian roommates knew about his affair and confronted him, but they didn't try to push him out of office—Ensign hung on for a long time until it appeared that he might face ethics charges over his efforts to cover up the mess. What don't those men have that Weiner did? Women in leadership positions in their party who had the power to damage their careers—and the desire to use it.

None of them lied to Nancy Pelosi.

I'm certain that my conservative friends will remind me of Nina Burleigh. (Read the second paragraph at this link.) But that was 13 years ago. And in 1998, there wasn't a woman in the land who could or did exercise political power over Bill Clinton. He did keep his office, you'll recall.

Why this is notable is that the Democratic Party makes real efforts to include women and minorities in power. Republicans snort at this, believing they believe in a more pure meritocracy that just happens to be weighted more toward white dudes. But that Democratic effort seems to have played a real role in how the Weiner scandal played out. That's neither good nor bad, but it's certainly different.

Remember, it was after Weiner confessed to his lewd online communications and vowed not to resign that House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi said he should resign: He'd lied to her, after all, claiming he wasn't responsible for the first incriminating photo. Pelosi was followed by DNC Chairwoman Debbie Wasserman Schultz. And there were lots of behind-the-scenes reports that Secretary of State Hillary Clinton—the friend and boss of Weiner's wife—was exceedingly furious with him. When Pelosi started the effort to take a powerful committee assignment from Weiner, the game was up: He quit. But the pattern is clear—the post-confession drive to get Weiner from office didn't seem to come from his constituents or even from Republicans, who seemed happy to let him twist in the wind. It came from powerful Democratic women.

Contrast this with some of the higher-profile Republican scandals of recent vintage. Sure, Christopher Lee resigned, but David Vitter went to see a hooker—and got re-elected! John Ensign's Christian roommates knew about his affair and confronted him, but they didn't try to push him out of office—Ensign hung on for a long time until it appeared that he might face ethics charges over his efforts to cover up the mess. What don't those men have that Weiner did? Women in leadership positions in their party who had the power to damage their careers—and the desire to use it.

None of them lied to Nancy Pelosi.

I'm certain that my conservative friends will remind me of Nina Burleigh. (Read the second paragraph at this link.) But that was 13 years ago. And in 1998, there wasn't a woman in the land who could or did exercise political power over Bill Clinton. He did keep his office, you'll recall.

Why this is notable is that the Democratic Party makes real efforts to include women and minorities in power. Republicans snort at this, believing they believe in a more pure meritocracy that just happens to be weighted more toward white dudes. But that Democratic effort seems to have played a real role in how the Weiner scandal played out. That's neither good nor bad, but it's certainly different.

Wednesday, June 15, 2011

Libya, Obama, and the War Powers Act

Remember during the Monica Lewinsky scandal when then-President Clinton responded to a question by quibbling with terms? "It depends on what the meaning of the word 'is' is," he told his interlocutors, and the moment became emblematic of Clinton's lawyerly slipperiness--not a great moment, even if you thought he was wrongly pursued.

Well, war is a lot more serious than a consensual affair in the life of a nation, but it appears that President Obama is determined to create a similar moment for himself:

Poppycock.

The War Powers Resolution is actually fairly clear on this, from my reading: Just because the United States is in a support role doesn't mean that President Obama can ignore the resolution. The act specifically states the president must report to Congress when U.S. forces "command, coordinate, participate in the movement of, or accompany the regular or irregular military forces of any foreign country or government when such military forces are engaged, or there exists an imminent threat that such forces will become engaged, in hostilities." It's not just when American trigger-pullers are pulling triggers, in other words, but when our forces are actively supporting other forces engaged in combat.

Under the most Obama-friendly reading of the circumstances—that we're only supporting the fighting countries, not fighting ourselves—he is still required to be accountable to Congress. Instead, his legal team has ignored the definition in the law and created its own.

I supported Obama in 2008 because he said things like this: "The President does not have power under the Constitution to unilaterally authorize a military attack in a situation that does not involve stopping an actual or imminent threat to the nation."

He lied. And he's trying to elide that fact with an unseemly parsing of words. How embarrassing. How wrong.

Well, war is a lot more serious than a consensual affair in the life of a nation, but it appears that President Obama is determined to create a similar moment for himself:

In a broader package of materials the Obama administration is sending to Congress on Wednesday defending its Libya policy, the White House, for the first time, offers lawmakers and the public an argument for why Mr. Obama has not been violating the War Powers Resolution since May 20.We're only a little bit at war, you see. Not even enough to count!

On that day, the Vietnam-era law’s 60-day deadline for terminating unauthorized hostilities appeared to pass. But the White House argued that the activities of United States military forces in Libya do not amount to full-blown “hostilities” at the level necessary to involve the section of the War Powers Resolution that imposes the deadline.

The two senior administration lawyers contended that American forces have not been in “hostilities” at least since April 7, when NATO took over leadership in maintaining a no-flight zone in Libya, and the United States took up what is mainly a supporting role — providing surveillance and refueling for allied warplanes — although unmanned drones operated by the United States periodically fire missiles as well.

They argued that United States forces are at little risk in the operation because there are no American troops on the ground and Libyan forces are unable to exchange meaningful fire with American forces. They said that there was little risk of the military mission escalating, because it is constrained by the United Nations Security Council resolution that authorized use of air power to defend civilians.

Poppycock.

The War Powers Resolution is actually fairly clear on this, from my reading: Just because the United States is in a support role doesn't mean that President Obama can ignore the resolution. The act specifically states the president must report to Congress when U.S. forces "command, coordinate, participate in the movement of, or accompany the regular or irregular military forces of any foreign country or government when such military forces are engaged, or there exists an imminent threat that such forces will become engaged, in hostilities." It's not just when American trigger-pullers are pulling triggers, in other words, but when our forces are actively supporting other forces engaged in combat.

Under the most Obama-friendly reading of the circumstances—that we're only supporting the fighting countries, not fighting ourselves—he is still required to be accountable to Congress. Instead, his legal team has ignored the definition in the law and created its own.

I supported Obama in 2008 because he said things like this: "The President does not have power under the Constitution to unilaterally authorize a military attack in a situation that does not involve stopping an actual or imminent threat to the nation."

He lied. And he's trying to elide that fact with an unseemly parsing of words. How embarrassing. How wrong.

Tuesday, June 14, 2011

Federalist 45: James Madison was wrong about (almost) everything

Returning to Federalist blogging after a too-long hiatus....

By now, I've made the point a few times that today's Tea Partiers have more in common with the original Antifederalists than with the actual framers of the Constitution. The Antifederalists wanted governance to remain primarily with the states, and while the Federalists certainly wanted more centralized federal governance than the Antifederalists, they still paid strong lip service to the idea that states would retain substantial power. The problem, some two centuries later, is that they were pretty much wrong about how that would play out—and nowhere is this more clear than in James Madison's Federalist 45.

Let's set the stage, though, by glancing at Antifederalist 45, written by "Sydney." He writes:

Federalist 45 is part of Madison's attempt to defend against this charge, and there are two things to note here. A) He resorts to shameless demagoguery. And B) in making the arguments about why states would retain substantial power, he was wrong about just about everything.

The evidence for A) comes when Madison offers his first argument. So you say the states are going to lose their power, huh? Why do you hate the troops?

If that sounds like exaggeration on my part, here's what Madison actually wrote:

But ugly political attacks always have been and always will be with us. For our purposes, it's more notable that Madison was really, really wrong in his central defense against the Antifederalists. Sure, he said, the Constitution empowers the federal government more than the Articles of Confederation—that's why we made it! But even under the Constitution, he says, "the State government will have the advantage of the Federal government."

It's easy to look at the landscape today and conclude Madison was wrong. That's the simple part. More complex is why Madison ended up being wrong.

By now, I've made the point a few times that today's Tea Partiers have more in common with the original Antifederalists than with the actual framers of the Constitution. The Antifederalists wanted governance to remain primarily with the states, and while the Federalists certainly wanted more centralized federal governance than the Antifederalists, they still paid strong lip service to the idea that states would retain substantial power. The problem, some two centuries later, is that they were pretty much wrong about how that would play out—and nowhere is this more clear than in James Madison's Federalist 45.

Let's set the stage, though, by glancing at Antifederalist 45, written by "Sydney." He writes:

It appears that the general government, when completely organized, will absorb all those powers of the state which the framers of its constitution had declared should be only exercised by the representatives of the people of the state; that the burdens and expense of supporting a state establishment will be perpetuated; but its operations to ensure or contribute to any essential measures promotive of the happiness of the people may be totally prostrated, the general government arrogating to itself the right of interfering in the most minute objects of internal police, and the most trifling domestic concerns of every state, by possessing a power of passing laws "to provide for the general welfare of the United States," which may affect life, liberty and property in every modification they may think expedient, unchecked by cautionary reservations, and unrestrained by a declaration of any of those rights which the wisdom and prudence of America in the year 1776 held ought to be at all events protected from violation.Viewed from a 2011 vantage point, this seems rather hyperbolic—Sydney asserts that the diminuition of state power will "destroy the rights and liberties of the people" and that seems incorrect. But it's surely the case that as the federal government has grown larger and more centralized that state governments have nonetheless also grown bigger and more expensive—and, in a lot of cases, funded by the federal taxpayer instead of just local folks.

Federalist 45 is part of Madison's attempt to defend against this charge, and there are two things to note here. A) He resorts to shameless demagoguery. And B) in making the arguments about why states would retain substantial power, he was wrong about just about everything.

The evidence for A) comes when Madison offers his first argument. So you say the states are going to lose their power, huh? Why do you hate the troops?

If that sounds like exaggeration on my part, here's what Madison actually wrote:

Was, then, the American Revolution effected, was the American Confederacy formed, was the precious blood of thousands spilt, and the hard-earned substance of millions lavished, not that the people of America should enjoy peace, liberty, and safety, but that the government of the individual States, that particular municipal establishments, might enjoy a certain extent of power, and be arrayed with certain dignities and attributes of sovereignty?If Sean Hannity claims the mantle of the Founders today, this is why it can sound plausible: Madison certainly sounds like a blowhard here. He opens not with a defense of the Constitution, but an attack on the motives of the Antifederalists—some of whom surely must've had some vested interests in the primacy of state governments, but some of whom opposed the Constitution based on their love of "peace, liberty, and safety."

But ugly political attacks always have been and always will be with us. For our purposes, it's more notable that Madison was really, really wrong in his central defense against the Antifederalists. Sure, he said, the Constitution empowers the federal government more than the Articles of Confederation—that's why we made it! But even under the Constitution, he says, "the State government will have the advantage of the Federal government."

It's easy to look at the landscape today and conclude Madison was wrong. That's the simple part. More complex is why Madison ended up being wrong.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

-

Just finished the annual family viewing of "White Christmas." So good. And the movie's secret weapon? John Brascia. Who'...

-

When rumors surfaced Monday that Philly schools Superintendent Arlene Ackerman might be leaving town, I was hopeful. Not just because her ad...

-

Warning: This is really gross. When the doctors came to me that Saturday afternoon and told me I was probably going to need surgery, I got...